Elements & issues

Timber construction

If one thinks of Sigfried Giedion’s Bauen in Frankreich (1928), iron and reinforced concrete were the building materials entrusted with the task to shape architecture during the Industrial Revolution. Only two years later, in 1930, Konrad Wachsmann’s book Holzhausbau led into that same modern wave a traditional material such as wood. Machineries produce a semi-finished material ready to be assembled on the construction site thus making obsolete the old artisanal crafts. Tenon and mortise have been replaced by a wide use of glues (for the production of laminated beams and plates) and by computerized milling machines that have made wood technology increasingly appealing and custom-oriented also to contemporary energy savings demands. Since the 1980’s in the Alpine and northern European areas, where many lumber processing plants expanded, there has been a renewed interest in this material and the various building techniques it provides: balloon and platform frame or structural panel construction. Burkhalter and Sumi in 1995 re-publish Wachsmann’s book highlighting limits and values in reference to the contemporary researches by F.L. Wright and R. Schindler. Beginning with the wooden building, Burkhalter and Sumi have developed a design grammar based on the correct relationship between of wall, roof and openings. The building by Deplazes in Sumvigt is one of the best examples of this resurging interest in wood architecture.

When wood reaches its structural limits in terms of span and height, it can be combined with other materials (i.e. steel and reinforced concrete) thus creating fascinating combinations like Peter Meili’s building in Biel – designed with Jürg Conzett as consulting engineer – where the building core is a pre-stressed reinforced concrete structure.

Read text

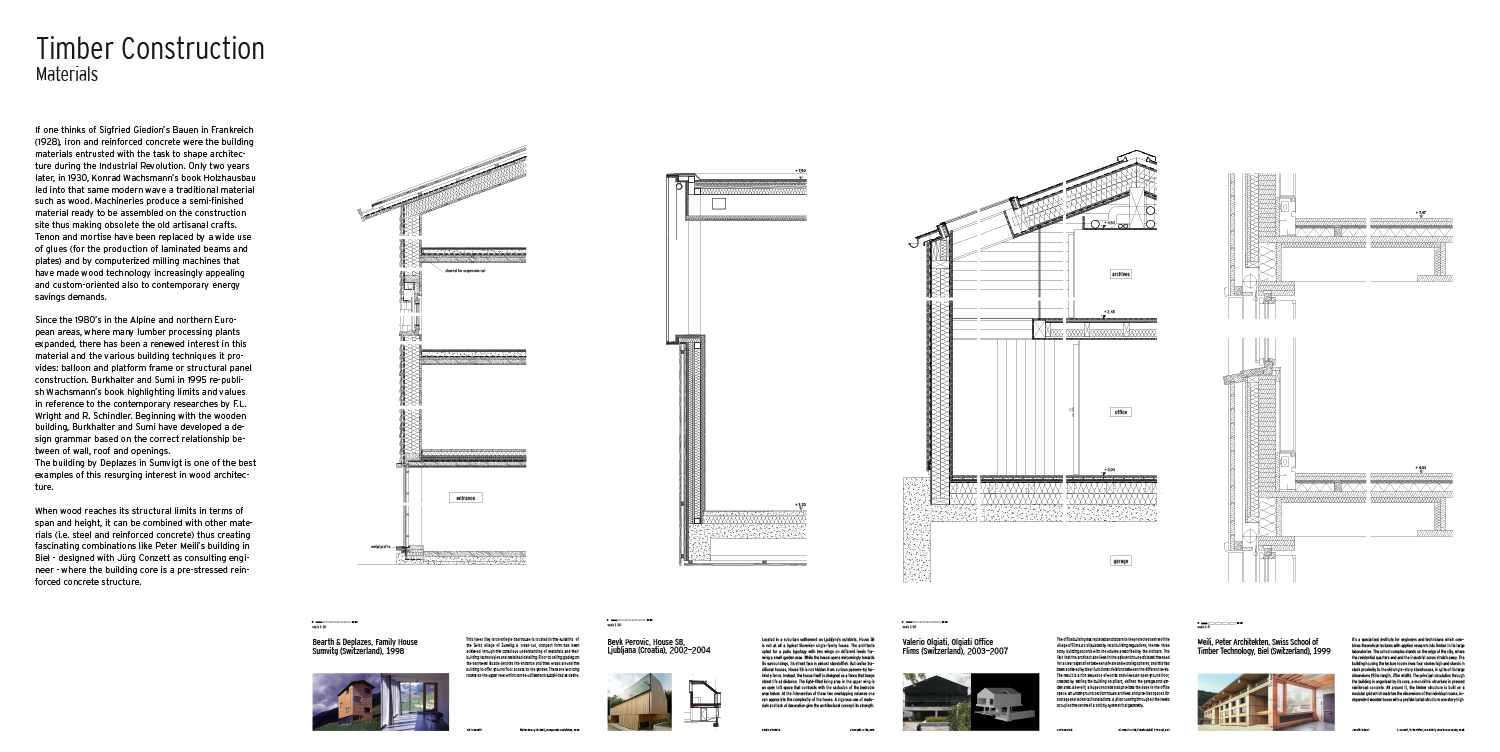

Bearth & Deplazes, Family House, Sumvitg (Switzerland), 1998

This tower like, larch-shingle clad house is located in the outskirts of the Swiss village of Sumvitg. A clean cut, compact form has been achieved through the conscious understanding of materials and their building technologies and restained detailing. Floor to ceiling glazing on the narrowed facade denotes the entrance and then wraps around the building to offer ground floor access to the garden. There are two long rooms on the upper level which can be utilized and subdivided as desire.

Silvia Danetti – Walter de Gruyter (ed.), Components and sistem, 2008

Bevk Perovic, House SB, Ljubljana (Croatia), 2002-2004

Located in a suburban settlement on Ljubljana’s outskirts, House SB is not at all a typical Slovenian single-family house. The architects opted for a patio typology with two wings on different levels fra-

ming a small garden area. While the house opens welcomingly towards its surroundings, its street face is almost standoffish. But unlike traditional houses, House SB is not hidden from curious passers-by behind a fence. Instead, the house itself is designed as a fence that keeps street life at distance. The light-filled living area in the upper wing is an open loft space that contrasts with the seclusion of the bedroom area below. At the intersection of these two overlapping volumes one can appreciate the complexity of the house. A rigorous use of mate-rials and lack of decoration give the architectural concept its strength.

Sergio Sbardella – El croquis n. 160, 2012

Valerio Olgiati, Olgiati Office, Flims (Switzerland), 2003-2007

The office building has replaced an old barn in the protected centre of the village of Flims. As stipulated by local building regulations, the new three story building accords with the volume prescribed by the old barn. The fact that the architect also lives in the adjacent house dictated the need for a clear separation between private and working spheres, and this has been achieved by blear functional divisions between the different levels. The result is a rich sequence of worlds and views.An open ground floor, created by setting the building on pillars, defines the garage and garden area. Above it, a huge concrete slab provides the base to the office space. An underground section house archives and provides spaces for storage and technical installations. A pillar running through all the levels occupies the centre of a strictly symmetrical geometry.

Carlo Damiani – El Croquis n. 156, Valerio Olgiati 1996-2011, 2011

Meili, Peter Architekten, Swiss School of Timber Technology, Biel (Switzerland), 1999

It’s a specialized institute for engineers and technicians which combines theoretical lectures with applied research into timber in its large laboratories. The school complex stands on the edge of the city, where the residential quarters end and the industrial zones stretch away. The building housing the lecture rooms rises four stories high and stands in stark proximity to the old single-story storehouses, in spite of its large dimensions (93m length, 25m width). The principal circulation through the building is organized by its core, a monolithic structure in pressed reinforced concrete. All around it, the timber structure is built on a modular grid which matches the dimensions of the individual rooms, independent wooden boxes with a prefabricated structure one story high.

Jennifer Adami – J. Conzett, M. Mostafavi, B. Reichlin, Structure as space, 2006