Contemporary architects

Burkhalter-Sumi – Timber cladding: facade / loggia

In their succinct essay “Form and Profession”, the only instance where they have written something close to a manifesto, Burkhalter Sumi observe that architecture and architects seem under attack from any number of quarters. He or she is increasingly impinged by the market forces and procurement methods under which the Anglo-American world already suffers. This is true even in Switzerland, where the architects has traditionally controlled the construction process and enjoyed considerable respect and autonomy. But the forecast demise of the profession through its disintegration now has such a long history that it forms its own tradition, they say with a Pop nonchalance, and has become its definition. They recount the split between the École des Beaux Arts and the newly founded Écoles Polytechniques, and briskly trace a series of crises through the Deutscher Werkbund, the various Bauhaus[es] and CIAM, reaching a climax in “1968 with demands that the discipline of architecture be broken into a series of subjects: economics, sociology, law etc.”. And from this chilling history of dissolution they calmly derive their precepts for being an architect: “First, the continual adaptation of our profession to an ever-changing environment is a sign, not of weakness, but of strength […] Like Roland Barthes’s Argonauts who continually renew their spaceship during flight, without ‘intermediate landing or interruption’, architects must also continually reconstruct the edifice of their theoretical knowledge.” But in a break with modernism’s confidence and a subsequent history of serial certainties, they acknowledge that the condition they describe involves one in a continual struggle, for, “It is not the elimination of […] conflicts, but their prompt resolution – the centring of the centrifugally dispersing demands and the consequent revelation of the hidden core – which constitutes the primary task of our profession.” […] The continual struggle described above is an ambitious definition of the architect, which ironically must manifest itself in a kind of humility, professional as well as formal. The clarity with which Burkhalter Sumi put it in “Form and Profession” belies the position’s complexity: “The discipline of architecture has […] its relation to society [as] its central concern […] The decisive question for us is whether the completed structure is capable of surviving everyday life […] Such an approach seeks an architecture which, at its best, has a self-evident character.”

Literatur: Steven Spier, Resolving the hidden core in: Burkhalter Sumi – recent works, 2g no 35, 2005 –

Read text

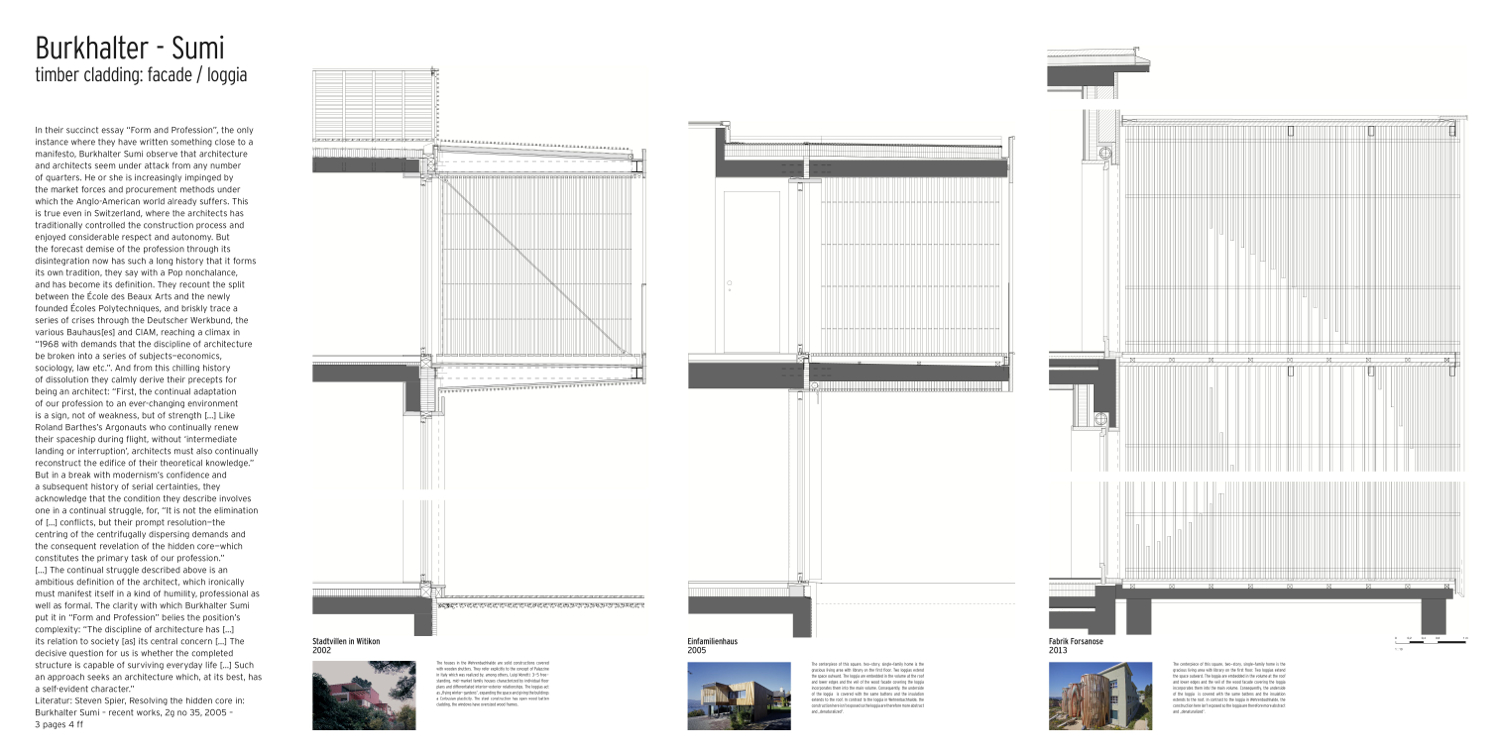

Stadtvillen in Witikon 2002

The houses in the Wehrenbachhalde are solid constructions covered with wooden shutters. They refer explicitly to the concept of Palazzine in Italy which was realized by, among others, Luigi Moretti: 3-5 free-standing, mid-market family houses characterized by individual floor plans and differentiated interior-exterior relationships. The loggias act as flying winter-gardens, expanding the space and giving the buildings a Corbusian plasticity. The steel construction has open wood batten cladding, the windows have oversized wood frames.

Einfamilienhaus 2005

The centerpiece of this square, two-story, single-family home is the gracious living area with library on the first floor. Two loggias extend the space outward. The loggia are embedded in the volume at the roof and lower edges and the veil of the wood facade covering the loggia incorporates them into the main volume. Consequently, the underside of the loggia is covered with the same battens and the insulation extends to the roof. In contrast to the loggia in Wehrenbachhalde, the construction here isn’t exposed so the loggia are therefore more abstract and “denaturalized”.

Fabrik Forsanose 2013

The centerpiece of this square, two-story, single-family home is the gracious living area with library on the first floor. Two loggias extend the space outward. The loggia are embedded in the volume at the roof and lower edges and the veil of the wood facade covering the loggia incorporates them into the main volume. Consequently, the underside of the loggia is covered with the same battens and the insulation extends to the roof. In contrast to the loggia in Wehrenbachhalde, the construction here isn’t exposed so the loggia are therefore more abstract and “denaturalized”.